Similar

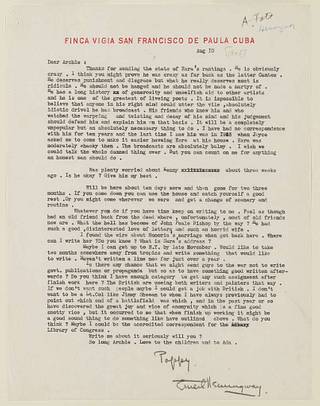

Letter, Ernest Hemingway to Archibald MacLeish discussing Ezra Pound's mental health and other literary matters, 10 August 1943

Summary

Reproduction number: A62 (color slide)

Novelist Ernest Hemingway (1899-1961) wrote this 10 August [1943] reply to his friend Archibald MacLeish (1892-1982), the distinguished poet and dramatist who served as Librarian of Congress from 1939 to 1944. Two weeks earlier, on 27 July, MacLeish had sent "Pappy" Hemingway negative photostatic transcriptions of recent inflammatory broadcasts made in Italy by their fellow American author Ezra Pound (1885-1972). The most influential poet and critic of his era, Pound had helped T. S. Eliot (1888-1965) create the landmark poem of the twentieth century, The Wasteland, founded the Imagist school of poetry, and befriended leading American and European writers. When he met Fascist leader Benito Mussolini (1883-1945) in 1933, however, Pound was so impressed with the Italian dictator's ideas that he later made radio broadcasts for the Axis powers which included strong anti-Semitic remarks.

As a result of his wartime broadcasts, Pound was indicted on 26 July 1943 in a United States District Court for treason, though MacLeish had suggested to Hemingway that "drivel" was a better term than "treason," which was "too serious a crime and too dignified for a man who has made such an incredible ass of himself." (Archibald MacLeish to Ernest Hemingway, 27 July 1943, in Letters of Archibald MacLeish, 1907 to 1982, ed. R. H. Winnick (Boston: Houghton Mifflin Company, 1983), 316.) Hemingway here agrees that Pound was "crazy," and indeed after Pound's arrest and return to the United States in November 1945, he was declared mentally unfit to stand trial. The insanity ruling was largely due to the intervention and support of literary colleagues, who respected Pound in spite of his unacceptable politics. Pound was incarcerated in St. Elizabeth's Hospital in Washington, D.C., until 1958, when he returned to Italy. During his thirteen years of confinement, he published more of his epic lifework, Cantos, which he had begun in 1924. In 1948 the Library of Congress awarded Pound the Bollingen Prize for poetry, a controversial choice which led the government to forbid the Library from henceforth administering the prestigious prize.

In this letter from MacLeish's papers in the Library of Congress, Hemingway also refers to Irish novelist James Joyce (1882-1941), who had met Pound in London literary circles earlier in the century. The final paragraph includes an appeal to MacLeish--then also assistant director of war information--to consider Hemingway for a position as a writer or correspondent covering the war for the Library. The novelist had been a volunteer ambulance driver in the First World War and subsequently published A Farewell To Arms based on those experiences. His 1940 novel For Whom the Bell Tolls had established him as a champion of freedom. Although MacLeish was unable to grant him accreditation, Hemingway did become a foreign correspondent during World War II. The Hemingway Papers, housed in the John F. Kennedy Library, Boston, Massachusetts, include MacLeish's side of this interesting literary correspondence.

Tags

Date

Source

Copyright info