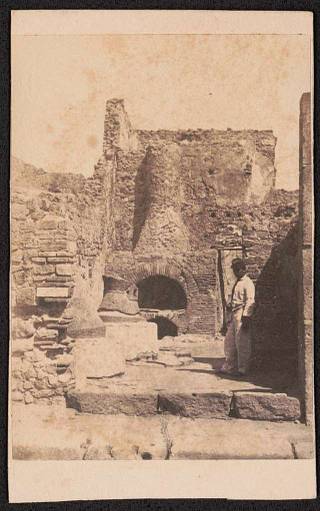

Unidentified African American soldier in uniform at ruined fireplace or oven, possibly at Fort Sumter

Summary

Notation on verso: "Black soldier, Fort Sumter."

Tax stamp on verso.

Gift; Tom Liljenquist; 2016; (DLC/PP-2016:144)

Purchased from: Steven J. Meadow, October 2015.

Forms part of: Liljenquist Family Collection of Civil War Photographs (Library of Congress).

pp/liljpaper

Named after revolutionary hero General Thomas Sumter, Fort Sumter was unfinished when the Civil War began. On December 26, 1860, six days after South Carolina seceded from the Union, U.S. Army Major Robert Anderson secretly relocated 127 men of the 1st U.S. Artillery to Fort Sumter thinking that it provides a stronger defense against South Carolina militia attacks. For a few months, South Carolina 's calls for evacuation of Fort Sumter were ignored by Union. On Friday, April 12, 1861, at 4:30 a.m., Confederate batteries opened fire on the fort, firing for 34 straight hours. After two hours, the Union started firing back slowly to conserve ammunition. During the fire, one Confederate soldier and two Union soldiers died. The next day the fort was surrendered. The Fort Sumter Union Flag became a popular patriotic symbol. Efforts to retake the fort began on April 7, 1863. After bombardment, the Union navy's started poorly planned boat assault: 8 Union sailors were killed, 19 wounded, and 105 captured. The Confederates did not suffer any casualties. The bombardment of the fort proceeded with a varying degree of intensity until the end of the war but the fort never surrendered. Sherman's advance forced the Confederates to evacuate Charleston and abandon Fort Sumter. The Union formally took possession of Fort Sumter on February 22, 1865. Fort Sumter was in ruins. After the war, the U.S. Army restored the fort and used it as a military installation until 1948 when the fort became a National Monument.

More than 2,500 special portrait photographs, called ambrotypes and tintypes, and small card photos called cartes de visite represent both Union and Confederate soldiers during the American Civil War (1861-1865). Tom Liljenquist and his sons Jason, Brandon, and Christian built this collection in memory of President Abraham Lincoln and the estimated 620,000-850,000 Union and Confederate servicemen who died in the American Civil War. For many, these photographs are the last known record we have of who they were and what they looked like. See "From the Donor's Perspective--The Last Full Measure" for the full story. The Liljenquist Family began donating their collection to the Library of Congress, Prints & Photographs Division in 2010, and continues to add to it. In addition to the ambrotypes and tintypes, the collection also includes several manuscripts, patriotic envelopes, photographs on paper, and artifacts related to the Civil War. The portraits often show weapons, hats, canteens, musical instruments, painted backdrops, and other details that enhance the research value of the collection. Other photo topics include flags, city views, veterans, and ships. Among the rarest images are sailors, African Americans in uniform, Lincoln campaign buttons, and portraits of soldiers with their families and friends. LOC Prints & Photographs Division holds thousands of images relating to the Civil War, found in many different collections.

Tags

Date

Location

Source

Copyright info

![[Unidentified young African American soldier in Union uniform with forage cap] [Unidentified young African American soldier in Union uniform with forage cap]](https://cache.getarchive.net/Prod/thumb/cdn18/L3Bob3RvLzIwMTkvMTEvMDUvdW5pZGVudGlmaWVkLXlvdW5nLWFmcmljYW4tYW1lcmljYW4tc29sZGllci1pbi11bmlvbi11bmlmb3JtLXdpdGgtZm9yYWdlLWNhcC1iYzM4MGMtNjQwLmpwZw%3D%3D/40/46/jpg)